How does shaft endmass affect squirt (cue ball deflection) and how is endmass related to stiffness?

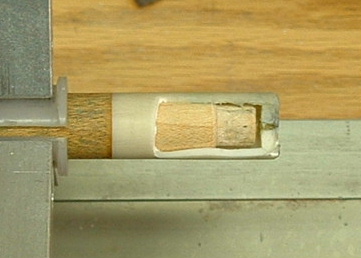

The characteristic that makes an LD shaft have less squirt (cue ball deflection) is reduced “endmass.” See Diagram 4 in “Squirt – Part VII: cue test machine results” (BD, February, 2008). People who think extra stiffness is required to produce more squirt are incorrect. Added endmass alone (without added stiffness) produces significant increases in squirt. This supports the theory in TP A.31. The squirt of a shaft can be lowered by reducing the weight of the last 5-8 inches. This can be done by reducing the shaft’s diameter, drilling out the core of the end of the shaft, using a lighter and/or harder tip (for more info, see cue tip hardness effects), and/or using a smaller (shorter), lighter, or no ferrule (which is heavier than wood). As demonstrated with the experiment in the article, mass closer to the tip has a greater effect on “effective endmass” than mass farther from the tip because it is moving more during tip contact (see what causes squirt); and beyond a certain distance, added mass has no effect at all. Here are cross-sections through common LD shafts (Predator 314 and the carbon fiber Revo) illustrating how the endmass is reduced:

Here’s a very illustrative example of what happens when you increase the endmass of a shaft:

“Endmass” is also related to lateral shaft stiffness. Firstly, a stiffer solid-wood shaft will typically be thicker and heavier at the end, resulting in more weight close to the tip. Secondly, with a stiffer shaft, the transverse (or lateral or shear) elastic wave will travel faster and farther down the shaft (from the tip) during the brief contact time between the tip and ball. The farther the wave travels, the larger the effective “endmass” will be, because more mass is being involved during contact with the ball. This effect can be clear with carbon-fiber shafts, where you would expect the end of the shaft to be much lighter (which tends to reduce “endmass”); however, because the end of the shaft can also be very stiff (which tends to increase effective “endmass”), the amount of squirt can be comparable to a wood shaft that might be little heavier at the end. Another potential issue with carbon-fiber shafts is that they don’t flex as much after a hit, so when you apply extreme spin (side, bottom or top), where the CB doesn’t move away from the tip as quickly, there is a chance for a double-hit (which won’t be directly noticeable, but the CB will appear to deflect or squirt more than expected). A wood shaft flexes more giving the CB room to clear away from the tip after the hit. If the end of the shaft is too stiff, this doesn’t happen as well and a double hit can occur at large tip offsets. For related info, see:

- “Coriolis was brilliant … but he didn’t have a high-speed camera – Part IV: maximum cue tip offset” (BD, October, 2005)

- “squirt,” “deflection,” “stiffness”

- cue “feel,” “hit,” “feedback,” and “playability”

- cue vibration resource page

- maximum sidespin resource page

As described above, lateral shaft stiffness can indirectly affect squirt by changing the effective “endmass” of the shaft. Lateral shaft stiffness can also have a direct effect on squirt since when a stiffer shaft is flexed (as the CB pushes the tip sideways), the shaft reacts with more sideways force, which can create more squirt. However, typical pool cue shafts are very flexible in the lateral direction (i.e., they don’t require much force to flex), and the shaft does not flex very much during the incredibly brief tip contact time anyway, so stiffness does not have a significant direct effect on squirt. Per the what causes squirt resource page, it is endmass (not shaft stiffness) that is almost entirely responsible for squirt. The following analysis shows how little shaft stiffness contributes directly to squirt:

TP B.19 – Comparison of cue ball deflection (squirt) “endmass” and stiffness effects

Tip hardness can also have an effect on effective endmass because a harder tip will have a slightly shorter contact time. Because the transverse (or lateral or shear) elastic wave won’t travel down the shaft as far during contact with a harder tip, the effective endmass and squirt can be less. However, a harder tip can also be denser and heavier, which would increase effective endmass and squirt.

For more information, see:

- NV D.15 – Cue and Tip Testing for Cue Ball Deflection (Squirt)

- NV B.32 – Squirt and the effects of endmass

- NV B.1 – Mike Page’s squirt and swerve video

- “Return of the squirt robot” (BD, August, 2008)

- HSV B.47 – effect of shaft endmass and squirt on miscue limit (for how the amount of squirt can affect the miscue limit)

- what causes squirt?

- tip hardness effects

- tip contact time

- shaft spine

Here’s a list of advantages and disadvantages of low-squirt shafts.

from iusedtoberich:

The Meucci shaft over the years has had features to reduce the endmass:

1. The ferrule has always been thin walled relative to most other cues. (the plastics used in ferrules is usually of higher density than maple)

2. The ferrule has been made of a less dense material than most other ferrules on competing cues.

3. On recent shafts (black dot), the tenon has been tapered like the end of a pencil (not that extreme), yet the internal walls of the ferrule have remained cylindrical. This further reduces endmass by introducing a tapered hollow region right behind the tip.

Here’s a photo from Cue Crazy (in AZB post) relating to “isuedtoberich’s” quote above, called Meucci’s Power Piston design:

What affect does shaft taper and the butt have on CB deflection?

If you make the tip end of a shaft (the last 5-8 inches) lighter, squirt is reduced. And if you change the mass or stiffness of the shaft beyond 5-8 inches, it has absolutely no effect on squirt.

Now, one must be careful to not confuse “squirt” with “the combined effects of squirt and swerve” (AKA “net CB deflection” or “squerve”). Swerve is affected by many factors including the speed of the stroke, the weight of the cue, the efficiency of the tip, the elevation of the cue, the properties of the ball and cloth, etc. Swerve (and not squirt) is what really makes aiming with sidespin over a wide range of shots challenging (and fun). So the taper and butt could affect “net CB deflection” or squerve.

Does a thicker shaft produce more squirt?

For a solid wood shaft of homogenous density, it is true that a thicker shaft will create more squirt, and for several reasons. The main reason is that the actual shaft mass close to the tip will be more. Also, the transverse stiffness will be larger. This creates two important effects. This will result in more sideways force as the shaft flexes (as the tip gets pushed sideways slightly as it rides the CB during the incredibly brief tip contact time). This is the effect that I show in my TP B.19 analysis to be extremely small. The other stiffness-related effect is that with a stiffer shaft, the speed of the elastic wave that travels down the shaft during tip contact will be faster, and this will increase the “effective endmass” of the shaft.

In your TP B.19 analysis, isn’t a 1.6% (or 14%) difference significant to a top player, where small differences are important?

It is important to understand the implications of the 1.6% (or 14%) result. The 1.6% (or 14%) applies to the 1.8° of total squirt, so the amount of squirt due to the flex-force effect is a whopping 0.027 (or 0.25)° (1.5% [or 14%] of 1.8°)!!! This angular difference is extremely small and not even measurable in a practical sense. No human could possibly detect or create an angle change of that magnitude. And even if a cue produced significantly more squirt as the example in my analysis, the flex-force effect would probably still be too small to distinguish (not to mention that the cue would be much more difficult to use at a pool table).

In your TP B.19 analysis, how does the flex-force impulse relate to the sideways impulse between the tip and CB?

The forward impulse (F_imp) on the CB is:

F_imp = m_ball*v_fwd

where m_ball is the mass of the CB and v_fwd is the forward speed of the CB.

For a given squirt angle “α,” the sideways impulse (S_imp) acting on the CB, which acts equal and opposite on the tip, is:

S_imp = F_imp*tan(α) = m_ball*v_side (1)

where v_side is the sideways speed of the CB.

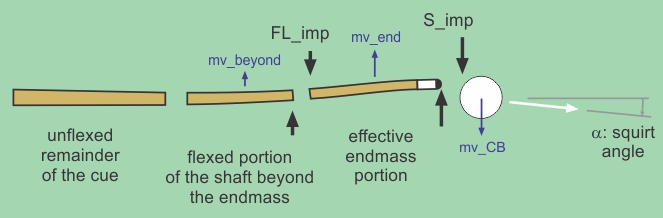

The “effective endmass” feels this impulse, but it also feels an impulse resulting from a shear force resisting shaft bending because the flexed shaft is pushing back on the endmass (and an equal and opposite force is felt on the remainder of the cue). This is illustrated in the following diagram. The “effective endmass” of the shaft involves only the 5-8 inches of the shaft closest to the tip. It flexes and acquires momentum during impact. However, the transverse or lateral or shear elastic wave travels farther down the shaft during tip contact (10-16 inches) since the elastic wave must travel to and back from mass for it to be “felt” by the tip during contact. Therefore, a portion of the cue beyond the endmass is also flexed and also acquires some momentum during tip contact. For a slightly different explanation and illustration, see the quote from Jal below. Also notice in the diagram below how the tip end of the shaft also flexes back toward the CB. This is due to the off-center hit on the tip. As the tip grabs the CB, the contact forces bend the shaft end toward the CB as the CB pushes the tip and shaft away with CB rotation. This tip-end flex action is visible in the super-slow-motion videos on the cue vibration resource page, and the overall push of the endmass away from the CB is clear in the illustrations and video on the what causes squirt resource page.

Notice that the only way the CB can be deflected (squirted) down (in the diagram) is if the tip is pushing it down (in the diagram). If the tip is pushing the CB down (in the diagram), then the CB must also be pushing back on the tip up (in the diagram), as shown by the equal and opposite S_imp arrows. This is why the end of the shaft gains momentum (mv_end) that causes it to flex out. This flex out continues after tip release due to the momentum imparted during tip contact. Again, this action is clear in the super-slow-motion videos on the cue vibration resource page.

The momentum balance equation for the whole system is:

m_ball*v_side = m_end*v_end + m_beyond*v_beyond

where m_end is the effective endmass of the shaft, v_end is the effective speed developed by the endmass, m_beyond is the effective mass of the flexed portion of the shaft beyond the endmass, and v_beyond is the effective speed developed by this mass. Note that in a typical simplified analysis of squirt and endmass (e.g., in TP A.31), the flex effect is neglected, resulting in a slightly larger effective endmass. Here, because some of the CB sideways momentum (m_ball*v_side) is offset by the momentum beyond the endmass (m_beyond*v_beyond), the endmass will have slightly less momentum (and therefore a slightly less effective endmass than in the simplified analysis).

The proper momentum equation for the endmass, taking into account the shaft-flex effect, is:

S_imp – FL_imp = m_end*v_end (2)

where FL_imp is the impulse of the force associated with the flex of the shaft acting on the endmass (and equal and opposite on the portion of the shaft beyond the endmass) during tip contact with the CB.

Substituting S_imp from Equation 1 into Equation 2 gives:

m_ball*v_side = m_end*v_end + FL_imp

Therefore, it is clear that the CB’s sideways momentum comes from two effects: the momentum transfer from the endmass (m_end*v_end) and the impulse of the flex force (FL_imp). Effective endmass is affected by lateral or transverse stiffness (as described in the main section above), but force due to flexing is a separate effect. This is clear because you can have one without the other. If most of the endmass were in the tip and ferrule, and the shaft had little or no stiffness (i.e., if it took little or no force to flex the shaft), there would still be the “m_end*v_end” effect but little or no FL_imp effect. And if the shaft end were stiff laterally but had negligible endmass (even though a greater length of the shaft would contribute to endmass), there would still be a “FL_imp” effect but little or no “m_end*v_end” effect. When the CB pushes sideways on the tip, it creates endmass momentum, but it also flexes the cue. Both of these things require force, hence the two terms in the equation above.

In the TP B.19 analysis, I am comparing the peak force involved with S_imp to the peak force involved with FL_imp. The flex effect is shown to be very small in comparison to the endmass effect.

There is a little “smoke and mirrors” going on here due to the awkward definition of “effective endmass” and because the flex force is actually a dynamic and distributed force acting along the “endmass” and beyond. Also, my static measurement of flex force and deflection doesn’t perfectly model the shaft flex involved with the sideways endmass motion. The effective length of the flex during tip contact is shorter than in a static deflection test (so the flex force will be larger). Although, with the Predator Z-2, the tip end of the shaft is very flexible with its small diameter (11.75mm) and hollow core (about 5 inches long), so a lot of the flex in the static case also occurs closer to the tip than the joint. Regardless, the analysis does provide good ball-park numbers.

Why does the end of the shaft flex close to the tip as shown in the diagram above?

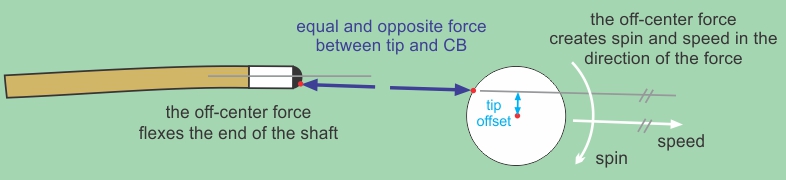

The diagram below illustrates this. The force between the tip and CB acts equal and opposite on each object. The CB speed is in the direction of this total force. The CB spin is created since the force’s line of action acts at a tip offset relative to CB center, creating a moment or torque. The equal and opposite force on the cue tip also acts off-center on the end of the shaft, creating a bending moment or torque. This is what causes the end of the shaft to flex.

Notice how the force from the tip pushes in the direction the CB heads (i.e., the force arrow is parallel to the speed arrow). This force has two components. One component acts to the right (in the diagram) on the CB and to the left (in the diagram) on the tip. This component is what pushes the CB forward in the line of aim of the shot, and causes the end of the shaft to flex as shown in the diagram (because the force acts off center on the tip). The other force component acts down (in the diagram) on the CB and up (in the diagram) on the tip. This component is what causes CB deflection (squirt) and causes the end of the shaft to gain momentum (speed) away from the CB (up in the diagram) that causes the shaft to flex out. This outward flex starts during tip contact (as the CB rotates during contact and pushes the tip away, as described and illustrated on the what causes squirt resource page) and continues after tip release due to the momentum imparted during tip contact.

How does the force between the tip and CB change during tip contact?

A tip behaves like a spring, where force is directly related to compression (F = kx). If the tip is compressed a little, it is because there is a small force acting on it. If it is compressed a lot, it is because there is a large force acting on it. When the tip first touches the CB, there is no compression at all, and no force. As the cue continues to move forward, the tip begins to compress gradually. This results in an equal and opposite force on the tip and CB that also increases gradually. The CB begins to accelerate as soon as there is a force acting on it (F = ma). The CB accelerates slowly at first since the force is small, but as the tip compresses more and more, the CB accelerates faster and faster. When the tip reaches full compression, the force between the tip and CB is at its peak, and the CB is accelerating at its fastest rate. As the CB begins to move faster than the tip, the tip begins to spring back and the force between the tip and CB starts to decrease in proportion to how much it is still compressed. The force is maximum at the beginning of the decompression and is zero after the tip has fully decompressed (as it is about to release from the CB), but there is force acting between the tip and CB during the entire spring-back or decompression stage. The force continues to cause the CB to accelerate forward this entire time (until the tip totally releases from the CB).

How can the tip and shaft end move away from the CB laterally if the CB is already gone when the tip and shaft move?

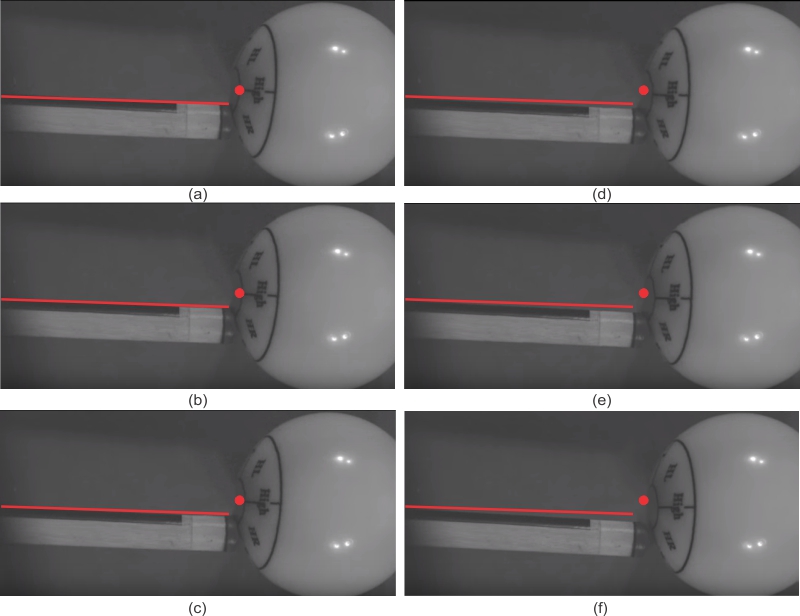

Acceleration (an increase in speed) can occur only with force; therefore, the CB can accelerate only while force is acting from the tip. Likewise, the tip and shaft can’t be given lateral speed, unless lateral forces are acting (during tip contact). The tip/shaft moves away laterally after the tip leaves the CB because the tip/shaft was given lateral speed during contact (while lateral forces were acting). It is the momentum (mass * speed) of the endmass that makes the tip and shaft move away from the CB after impact. Now, any flex energy still stored in the end of the shaft after tip release will also cause some post-release vibration (as is evident in the slow motion videos on the cue vibration resource page), but this is independent of (and much smaller in amplitude than) the larger-scale tip/shaft motion away from the ball (due to the endmass lateral momentum), as is evident on the what causes squirt and cue vibration pages. Below are some stills from a super-slow-motion video showing of motion of the tip, CB, and shaft evolve during and just after contact. The red line marks the initial position of the top of the shaft and initial tip contact point, and the red dot marks the initial position of a distinct point on the ball. They are in the same positions in each successive image. It is clear that the tip and shaft move down (laterally) away from the CB as the CB moves forward with increasing speed and spin during the entire period of tip contact.

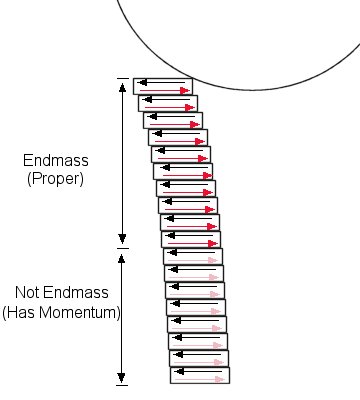

from Jal (in AZB post):

As the transverse (shear) wave travels down the shaft, it has to be reflected back off the medium in which it’s propagating and reach the tip again in order to be felt by the cueball. If you divide the shaft into thin sections, when the wave reaches an interface between two sections, the leading section first transmits the shear force to the trailing section. The trailing section then, naturally (Newton’s Third), produces a reaction force, equal an opposite, which then travels as a wave (disturbance) back toward the tip. Here’s sort of an illustration with the black arrows indicating the original shear and the red ones indicating the reactions.

Note: Maybe I should have reversed the locations of the black and red arrows in each section for better clarity.

As you get farther down the shaft, there isn’t enough time for the reflected waves to return all the way to the tip. This is indicated by the pale red arrows. However, in this region, the sections are 1) moving to the left (have momentum), and 2) the reaction forces they’re generating, while not reaching the tip, are slowing down the upper section whose reaction forces are reaching the tip.

Therefore, since we define “endmass” to be the mass that, from being pushed aside, produces a counter-force that acts on the cueball, only the upper section fits the bill. It (the upper section), being slowed by the reaction forces from the lower section, does not posses all the equal-and-opposite momentum of the cueball – the lower section carries part of it. Thus, there must be more force acting on the cueball than we can account for from the endmass (proper) alone. That force must be the restorative (flexing) force generated by the bend, since the lower section can’t contribute – its waves never reach the tip.

How can you be so sure shaft stiffness and flex has no significant direct effect on squirt?

1.) Shaft endmass can be increased significantly by adding mass close to the tip (e.g., by using a heavier tip or ferrule, by inserting something heavy but not stiff into a cored-out shaft, or by physically adding external mass to the tip end of the shaft). This has been clearly demonstrated with numerous experiments by me, Mike Page, and others. In these cases, the endmass is increased dramatically with no increase in shaft stiffness.

2.) Removing endmass from a shaft without significantly changing the stiffness of the shaft (e.g., by using a lighter ferrule and/or by drilling out the core of the shaft end), can significantly reduce the amount of effective endmass and squirt. This has also been demonstrated with the design of Predator shafts. Drilling out the core does not have a significant effect on shaft-end stiffness, but it does dramatically reduce endmass and squirt (as does the lighter ferrule).

3.) As my TP B.19 analysis shows, the total sideways force acting between the tip and CB is due to two physical effects. Part of the force contributes impulse which imparts momentum to the endmass of the shaft. The other part of the force (much smaller) is required to flex the shaft. The end of the shaft effectively looks like a mass supported by a spring. Think of a simple diagram of a linear spring-mass system with an applied force pushing on a mass supported by a spring. Some of the force applied to the mass goes into accelerating the mass (imparting momentum), and some goes into compressing the spring (i.e., F_applied = ma + kx). The resultant force experienced by the mass is not the force applied to the mass (F_applied); rather, it is the amount of excess force not being resisted by the spring (F_applied – kx). As described above, this same logic applies to the squirt-endmass-stiffness problem. The difference between the shaft-endmass-lateral-stiffness problem and the simple linear-spring-mass problem is that the total endmass of the shaft depends on shaft stiffness (in addition to the weight of the tip, ferrule, and anything else on or in the end of the shaft), but the spring force is still there.

… but what if the shaft were extremely light but very stiff laterally?

A very stiff cue (with very little lateral flexibility) would be useless. The amount of effective endmass and CB deflection would be large, and the direct stiffness effect would be a big factor (unlike with actual pool cues that are very flexible laterally).

FYI, carbon fiber shafts come about as close as physically possible to this “thought experiment.” They are strong and stiff enough (longitudinally and laterally) while keeping the end of the shaft as light as possible. The lightness of the shaft end is the dominant factor in reducing CB deflection (squirt). I have done a lateral flex comparison of my carbon fiber Revo to my wood Z-2 (by bending them with a lateral force at the tip), and the Revo is stiffer laterally, but they have very close to the same CB deflection (see NV J.12).

Mike Page and I have done tests showing that changing shaft stiffness of an actual pool cue (without changing endmass) has very little affect on squirt. See Diagrams 2 and 3, and the surrounding discussion, in “Return of the squirt robot” (BD, August, 2008).

There have also been many experiments showing what happens when the endmass is changed without changing lateral stiffness. For example, see Diagram 1 and the surrounding discussion in the same article.

Also take a look at the following tests and analysis that shows how small the direct stiffness effect is compared to the endmass momentum effect:

TP B.19 – Comparison of cue ball deflection (squirt) “endmass” and stiffness effects

How does one go about measuring shaft transverse stiffness (e.g., to compare two different shafts)?

To measure the “transverse stiffness” important in discussions concerning squirt (CB deflection) and endmass, rigidly support the entire cue on a table (with clamps and/or heavy weights) so only the portion “active” during tip contact is hanging over the edge of the table. “Endmass” involves only the 5-8 inches of the shaft closest to the tip, but the transverse wave travels farther down the shaft during tip contact (10-16 inches) since the transverse wave must travel to and back from mass for it to be “felt” by the tip during contact, so I suggest 8 inches (as a good average value of flex length during tip contact). Then hang a weight from the tip and measure how much the tip moves down (i.e., how much the shaft end flexes). The transverse stiffness is:

k_trans = (weight applied to tip) / (distance tip moves down)

See TP B.19 for an example calculation (using the measurement I took with a Predator Z2 shaft).

The shaft transverse stiffness is inversely proportional to the amount the shaft flexes. With a smaller stiffness, the shaft flexes more; and with a larger stiffness, the shaft flexes less. It is important to not confuse the “deflection” of the shaft (how much the tip moves down when the weight is applied) with the CB “deflection” caused by the shaft. A shaft that “deflects” more will usually produce less CB “deflection” (squirt), unless the tip and/or ferrule and/or shaft end are heavy.

The “stiffness” or “whippiness” a player “feels” applies more to the entire cue. That could be quantified similarly by extending more of the cue over the edge of the table or by measuring frequencies (rates) of vibration of the cue during a hit (e.g., with an accelerometer). Although, there are many factors that affect the “hit” or “feel” of a cue.

How much of an effect does added or removed endmass have on the resulting squirt of a shaft?

Based on the theory in TP A.31 and the data in “Squirt – Part VII: cue test machine results” (BD, February, 2008), a typical cue might have a ball-to-endmass ratio of about 30, corresponding to an effective endmass of about 5 grams. Any endmass added to or taken away from this would affect the amount of squirt proportionally. For example, for the 0.3 gram and 1.3 gram added massés in Diagram 4 of the article, the total endmass would be 5.3 with 0.3 grams added close to the tip and would be 6.3 with 1.3g added close to the tip. This comparison corresponds to an endmass ratio of 6.3/5.3=1.2. The robot measurements for squirt angle were 3.9° with the larger added mass and 3.3° with the smaller added mass. This is directly related to the endmass ratio: 3.9/3.3 = 6.3/5.3 = 1.2.

from Bob Jewett (in AZB post):

The stick transfers energy to the cue ball by compressing like a spring along its whole length. The compression wave happens at the speed of sound in the stick, which is about 13000 feet per second. This speed is the fastest that the butt can learn of something colliding with the tip. Some people make the mistake of thinking of the cue stick as being perfectly rigid and incompressible, but it’s not. So, the shot proceeds like this: the stick is coming forward and the tip meets the ball. The tip starts to compress, force and acceleration of the cue ball start to build up. The ball also starts to compress, since it too is not incompressible. The ball has started to move, but is not up to the speed of the stick yet, and the stick has started to slow down as its energy is transferred to the cue ball. This continues until the tip (and ferrule and joint and butt) reach maximum compression along the length. At this exact point some amazing things are happening. The stick and ball are moving at the same speed. The force between stick and ball are at their maximum. The compression along the length of the stick (including the tip) is at its maximum. The energy stored in the spring-like compression of the tip (and stick and ball) are at their maximum. For a typical ball and stick, the speeds of the ball and stick are 75% of the original stick speed.

After this point of maximum compression, the ball is pushed forward from the tip by the compression of system. The ball starts to move even faster from this force and the stick continues to slow down. This “unwinding” process continues until the ball finally leaves the tip. At that point, the ball is going at about 130% of the original stick speed, and the stick has slowed down to about 50% of its original speed. (The 130% would be 150%, but the tip is not perfect in springing back to its original shape, and energy is lost.)

Now the hand comes in. Human flesh makes a much “softer” spring than the leather of a tip or the wood that is compressed along the length of the stick. Think of the tip as about the stiffest car spring you can imagine and your hand like a rubber band. The cue ball is gone by the time your hand — which is still moving forward at full speed — can wind up even a little. As the hand winds up on the stick and relaxes, which takes about 20 milliseconds, the hand is slowed to about 80% of its initial speed and the stick goes from 50% back up to 80% of its initial speed. Of course this re-acceleration of the stick by your hand is useless in that the cue ball is long gone.

How does a heavier stick affect things? It changes that 130% number. The formula is in Byrne’s Advanced book, and somewhere in my columns in Billiards Digest and certainly in Ron Shepard’s paper and Dr. Dave’s book. A heavier stick through the spring action, puts slightly more energy into the cue ball.

As for how the weight of the stick affects the squirt, I think the answer is that it doesn’t, much. Squirt is caused by the spinning cue ball pushing the stick to the side during the contact time of an off-center hit. The amount of squirt is determined by the mass that is being pushed to the side. Since the stick is very floppy side-to-side (as compared to length-wise compression), only the front part of the stick can participate in the squirt during the 1 millisecond or so of contact time. A heavier stick will increase the contact time a little, and that will increase the squirt a little, but I think this effect is pretty small.

Phrased technically, the transverse wave has a very slow propagation velocity along the length of the stick, and so the joint and butt cannot participate in the sideways push that causes squirt.You should find Mike Page’s discussion of his experiment with vise grips on the shaft which determined how much of the shaft participates in squirt.

As Fred mentioned, a major problem with some of the Jacksonville Project was that Iron Willie had too stiff a grip — like vise grips — and too hard a bridge. I have heard that Predator’s current cue testing robot has fixed those problems to hold the cue more like a human at both ends.

As for some of your other questions, in theory the squirt should depend on stiffness of the cue since that should change the speed of the transverse wave. In practice, “end mass” seems to be a much better indicator of squirt than stiffness. There are stiff cues with little squirt and stiff cues with lots of squirt. A major red herring along the path of squirt studies was the fact that carom cues tend to be stiff but have relatively low squirt. They usually have smaller tips than pool cues.

reply from Dr. Dave:

For those who want more information related to Bob’s post, further descriptions, illustrations, and demonstrations can be found on the following resource pages:

what causes squirt?

endmass and stiffness effects

shaft squirt (CB deflection) testing

cue tip hardness effects

effects of light vs. tight grip

Concerning how the cue and CB speeds vary with tip offset from center, cue weight, and cue speed, that is covered in detail (with physics and math) in: TP A.30 – The effects of cue tip offset, cue weight, and cue speed on cue ball speed and spin.

Dr. Dave keeps this site commercial free, with no ads. If you appreciate the free resources, please consider making a one-time or monthly donation to show your support: