How does the speed and acceleration of the cue vary during a typical stroke?

See the following videos:

Bob Jewett also has an article with a good example plot here (see page 9).

A study document in “Movement Variability of Professional Pool Billiards Players on Selected Tasks” shows that most elite pool players reach maximum cue speed (with zero acceleration) at the moment of impact with the CB (except for power break shots).

All stroke types create acceleration during the forward stroke. They just do so different amounts at different times. With a typical pendulum stroke (and most strokes of good players, which are usually pendulum style into the ball, regardless of what happens during the follow through), acceleration occurs during the entire forward stroke, but diminishes to zero as you approach the ball. Acceleration is the rate of change of speed. If there is no (or very little) acceleration just before CB contact, the speed is no longer increasing as the tip hits the ball. Therefore, the cue is not accelerating “into” the ball. The speed levels off just before CB contact. This makes it easier to have better speed control because the speed isn’t changing as you hit the ball; otherwise, slight changes in stroke “timing” can result in different speeds. So there might be an advantage to not accelerate “into” the ball. People who drop their elbow before CB contact are more likely to have slight acceleration (with the cue speed is still increasing) at CB contact, especially with power shots. If so, so they are accelerating “into” the ball. Although, cue acceleration at tip contact really doesn’t do anything for you. You don’t want to decelerate into the CB, but acceleration during tip contact is also undesirable (in general) since it means you didn’t accelerate soon enough or didn’t use a long-enough stroke to reach the desired speed at contact. The cue does all the work during impact, with very large force at the tip over an extremely short amount of contact time. The grip hand has practically no influence during tip contact per the info on the grip effects page. For more information and demonstrations, see:

from Bob Jewett (in AZB post):

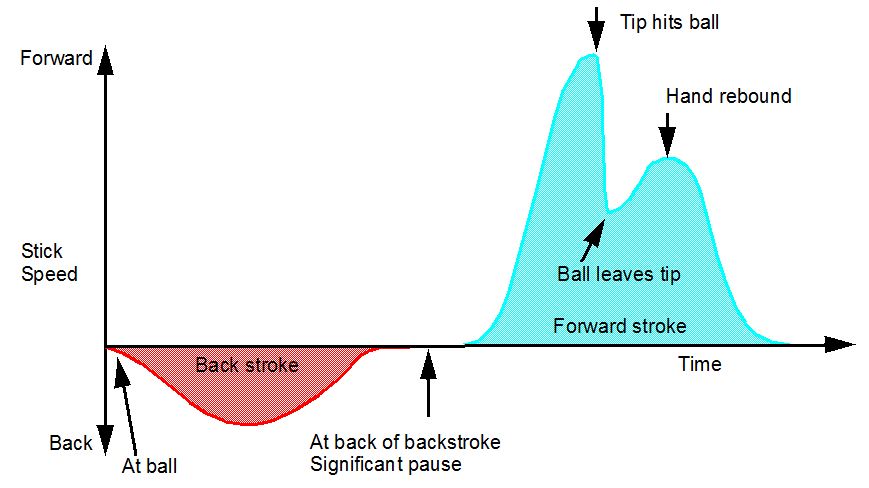

The first plot shows a longer pause at the end of the back stroke. Players who have what I call a “significant” pause will keep their cue all the way back and without motion or acceleration for half a second or a second or so.

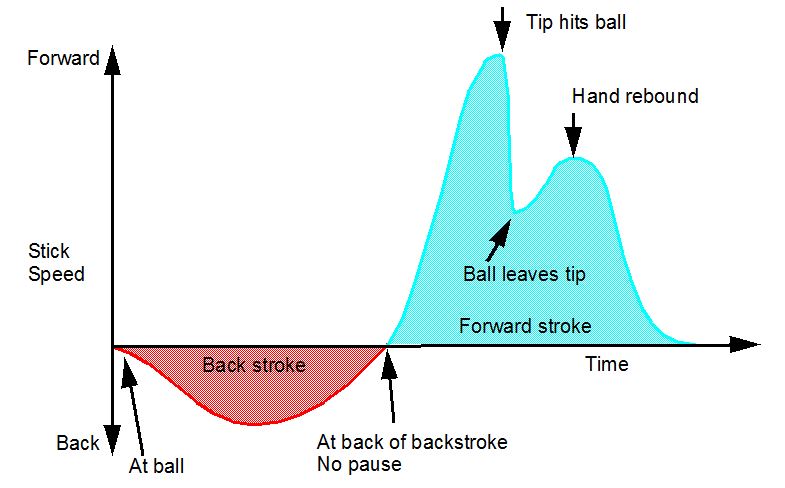

This final stroke timing has no pause at the end of the back stroke. When the cue gets to its farthest back position, the arm/hand is already pushing forward accelerating the cue stick forward. There is no time when there is both zero motion and zero acceleration, which is how I define a pause.

What do people usually mean when they say “accelerate through the ball” or “finish the stroke?”

They mean: “don’t decelerate into the ball” (i.e., don’t slow the cue before cue ball contact). Decelerating into the ball (i.e., “letting up on the stroke”) can result in very poor speed control. For more info on the effects of speed and acceleration, see: follow through.

See also: TP B.4 – Stroke speed and acceleration vs. distance. Here is the summary from the analysis:

With typical pendulum (p) strokes, the speed is more constant (i.e., leveled-off) at CB impact, possibly making it easier to control shot speed, because the speed is less sensitive to variations in bridge and stroke length. With typical “accelerate into the ball” (a) strokes, the force increases and levels off during the stroke, and force is being applied all of the way up to ball impact. With a classic pendulum stroke, it is natural to coast into the ball with no force at impact. The peak force is typically lower with an “accelerate into the ball” stroke than with a pendulum stroke (for the same shot speed) because force is applied over a larger distance. Therefore, for some people, this type of stroke might seem to require less effort for a given speed, and higher speeds might be possible. A typical “accelerate into the ball” stroke usually involves more of a “piston-like” stroke, with shoulder motion and elbow drop, allowing some people to generate force more easily throughout the stroke. One disadvantage of a piston stroke is that tip-contact-point accuracy might be more difficult to control.

TP A.9 – Cue accelerometer measurements shows accelerometer measurements and describes cue reactions during strokes and CB impacts. The blue curves in the top three plots (red curves in the bottom two plots) represent forward acceleration. A positive acceleration implies slowing in the backward direction (e.g., at the end of the back swing) and/or speeding up in the forward direction (e.g., during most of the pre-impact portion of the forward stroke). A negative acceleration implies slowing in the forward direction (e.g., in the later part of the forward warm up strokes) and/or speeding up in the backward direction (e.g., at the beginning of the backstroke).

The relatively flat portion of Andreas’ curve, before impact, corresponds to the second half of his back-swing. Notice how it is nearly identical to the shapes in the warm-up strokes (which I think are fairly firm). I think the entire forward stroke, before impact, is represented by the tall peak. The final forward stroke is much faster and more forceful than the warm-up strokes. After the peak, and before impact, the acceleration appears to go negative a little, implying he was actually decelerating a little before impact (if you trust the sensor, its calibration, and the data acquisition). At impact, the signals go wild due to shock waves and vibration.

In the first two plots (softer strokes), the acceleration is still positive at impact, implying that the cue stick is speeding up during the entire forward stroke (e.g., he is accelerating into the ball). Both of Pizutto’s plots show slight slowing (negative acceleration) just before impact.

Andreas does not appear to have a distinct pause at the transition between the back and forward stroke because the acceleration curve would be flat (at zero) if there were a deliberate pause.

The spike before impact represents the entire forward stroke, not any weird wrist action. Note that the time scales are very different between the two sets of plots. Pizutto’s plots are just showing the final forward stroke and the resulting shock and vibration immediately after impact. Andreas’ plots show a much large time interval, including warm-up strokes.

If I accelerate into the CB, will I get more “juice” on the ball?

from Jal:

In principle, the cueball will … have more speed and spin … when you apply a force during impact. It’s just that since the impact period is so short (mainly), the effect is essentially negligible. If you had a really, really soft tip such that contact lasted, say, a second, that would be a different story. So would being able to apply something like 100 lbs of force, as opposed to what we actually apply, about 15-20 lbs at the peak of a power stroke (much less throughout most of the rest of the stroke).

That aside, “accelerating through” can, in theory, give you noticeably more [“juice”] by generating more cue speed before impact commences. Once impact begins, virtually nothing short of a superhuman effort can alter things. And the term “accelerate through” is a misnomer. You can continue to apply force, but the impact will inevitably slow the cue down unless you can muster something on the order of 400 lbs.

[The cue] does sense force, but the force doesn’t last long (it takes force acting over time to get things moving). And the entire force that you might be applying with your grip hand is not what the cueball sees; it’s only about 1/4’th of that. The force that really gets its attention is the one generated by the impact of the already moving cue, and this can approach 300-500 lbs. That’s why cue speed is important, not the relatively meager force generated by our stroking arm.

Dr. Dave keeps this site commercial free, with no ads. If you appreciate the free resources, please consider making a one-time or monthly donation to show your support: