What are some insightful quotes about the CTE aiming system?

from mohrt, concerning step 4 of the CTE experiment:

mohrt: What you are doing “different” for every single shot is acquiring a unique visual for the given shot (which means a unique physical eye position for the given perception.) Many shots share the same alignment and pivot. But the perception is always unique. This is what leads to a unique connection for each and every shot line. As for determining when an alignment changes from one to the next, that comes from experience.

dr_dave: Based on your explanation, I would describe how CTE Pro One “actually works” like this: The pre-shot routine fostered by CTE Pro One creates a methodical framework that allows one to visualize and aim each shot more consistently and effectively. The alignments and pivots don’t do the aiming for you. You still need to “acquire a unique visual” for a given shot and “perceive” the necessary line of aim on which you must place the fulcrum of your bridge (so the pivot brings you to the necessary line of aim for the shot).

from AtLarge (concerning Version 4):

If performed robotically, Stan’s CTE is a discrete aiming method (“x-angle system” in pj’s terms) rather than a continuous aiming method. That means, on paper, that it offers only a limited number of cut angles for any given distance between the CB and OB. If the CB-OB distance changes, you get another set of cut angles.

In use, however, I believe many players actually convert it into something more flexible (more cut angles) by slightly modifying something either before or after the pivot, based upon their knowledge of where the pocket is. I think those “feel” adjustments can become so routine and ingrained that the method starts to seem like a continuous method (unlimited cut angles at any CB-OB distance).

I’ll say again what has been said many times about why it is an “x-angle” system. Let’s say we’re talking about cuts to the left. Stan’s method calls for sighting the CB center to the OB right edge. That’s the CTEL. Now, we have a secondary alignment line and a pivot direction to choose. But the menu offers only 6 choices for these: A with right pivot, A with left pivot, B with right pivot, B with left pivot, 1/8 to 1/8 with right pivot, and 1/8 to 1/8 with left pivot.

Assume the CB and OB are 3 feet apart. Place them anywhere on a flat surface. Forget about any pocket for now. Stan’s method, if performed robotically for the two balls 3 feet apart, offers just 6 ways to align yourself, i.e., 6 ways to determine the final direction of aim of the cue stick. You could run through the entire menu of 6 ways to cut the OB to the left, replacing the two balls identically each time. You’ll get 6 different lines of travel for the OB, i.e., 6 actual cut angles. Repeat the drill as many times as you want to with a 3-foot separation between the balls. You have only 6 menu items or 6 sets of instructions. If you do each of them the same way each time, you’ll get the same cut angle each time for each of the 6 alignment-menu selections.

Now transfer the two balls to a pool table, but keep them 3 feet apart. You have the same 6 menu items or sets of instructions. If you perform them the same way, you should get the same 6 cut angles. But now, you have an intended pocket for the OB. This, at last, means you must choose just one of the 6 menu items for alignment. If you choose the best of the 6, and perform your alignment exactly as you did on the flat surface with no pockets, you should get the same cut angle that you did on the flat surface with no pockets. That actual cut angle may or may not be the cut angle necessary to pocket the shot. What increases the likelihood that the shot will be pocketed is that the player now knows precisely where the pocket is. His “visual intelligence,” as some have called it, allows him to slightly modify something in his visuals, or in his stance, or in his approach to the table, or in his offset, or in his pivot, or … in something. And that adjustment, be it conscious or subconscious, converts the 6-angle system into a more continuous system (far more cut angles for that 3-foot CB-OB distance).

from AtLarge (concerning Version 4 above):

dr_dave: For a given CB-OB relationship and cut direction, there is only one vertical plane or line through both the center of the CB and the outer edge of the OB (i.e., the CTEL), in 2D or 3D. If you are able to visualize more than one, that might explain how you are able to create a wide range of cut angles for a given CB-OB relationship (i.e., with the CB and OB a fixed distance apart).

AtLarge: Exactly, Dave. When users talk about the outermost edge or rotating edges, they must just be referring to viewing that plane, or a line in that plane, from a slightly different angle (i.e., the “vision center” isn’t in that plane).

stan shuffett: If a player’s eyes were positioned exactly the same for each shot, A and B, the results would be identical. …[but]…The eyes are in different positions for each shot. …Just because a CB and an OB share a common distance and the same visuals does not mean the eyes will be positioned the same way for each shot. Perception is altered with varied eye positions. …

AtLarge: What is it, then, that guides the positioning of the eyes other than the CTEL and the secondary alignment line. I was under the impression that those two lines force an eye placement that “locks in” the two relevant edges of the CB and, therefore, control the pre-pivot cue alignment. The answer must have something to do with the actual pocket (target), right? Would you not call that something “visual intelligence” or “feel”?

stan shuffett: I would call it experience. Experience is our major teacher. … I use the word experience as a reference to knowledge. …

AtLarge: I take this input from Stan as revelatory. He is acknowledging that the basic set of prescriptions, if executed precisely the same way every time, would create only a small number of cut angles for a given CB-OB distance. So that issue should be settled. What, then, creates the additional cut angles; what turns a discrete method into a continuous method — one with enough cut angles to pocket all shots? Where is the “feel” being introduced? Stan has now answered that question — it is different eye positions for the same set of visuals. In other words, for any particular shot and alignment-menu choice, such as this:

CB-OB distance = 3 feet

cut to left

secondary alignment line to “B”

bridge length = 8″

cue offset = 1/2 tip

pivot from left to rightmultiple cut angles can be achieved by viewing the CTEL and secondary alignment line from different eye positions.

How does one know where to put his eyes? It is knowledge gained from experience. Stan did not acknowledge that this is “feel,” but I’m sure many of us would view it that way, as feel in any aiming method is developed from experience in using the method.

So there we have it. Stan’s manual CTE depends upon utilizing multiple eye positions within each of the basic 6 alignments. The feel or additional knowledge is not introduced by varying the offset, or by varying the bridge length (beyond what Stan prescribes), or by fudging the pivot — it comes from knowing where to place the eyes while still somehow holding to the underlying pair of visuals for each of the prescriptions.

I hope this really puts an end to the squabbles. Manual CTE is not some voodoo hocus pocus. It is not geometric magic. There are no supernatural powers to align-&-pivot methods. It doesn’t work because of numerology — the table being 1×2 or 90 being the sum of 45, 30, and 15. It works by utilizing a small number of reference alignments that the player has learned to fine tune based on his explicit knowledge of where the pocket is and the appearance of the cut angle needed for the shot, i.e., his experience-based knowledge of the shot needed.

dr_dave: I would add to your synopsis that CTE can also provide many other potential benefits to some of its users.

from Patrick Johnson (concerning Version 3 above):

First, what I think it is: I think CTE is a “reference” aiming system (very similar in concept to, and in fact an outgrowth of, Hal Houle’s old “3-angle” system), that divides all the possible shots into two categories (thinner or fuller than half ball), leaving the final aim adjustment up to you to learn “by feel”. I think it adds some suggested “systematic” adjustments, but nobody can seem to describe those, which makes me think they’re probably mostly learned by feel too.

How it works/what it offers: I think CTE offers its users the following things:

1. A specific and easy-to-see starting place (the half-ball alignment) that’s in the middle of all the possible alignments. Each shot can be “measured” in relation to the half-ball alignment, giving some structure to an otherwise wide-open (and maybe daunting) narrowing-down process. (This is also the way the old 3-angle system worked, but with three reference angles rather than just one.)

2. A specific and easy-to-see starting alignment of the stick, CB and OB (again, the half-ball alignment) that brings your focused attention to how those three things are aligned, something very helpful in learning to aim (and in executing aim once you’ve learned it) but often overlooked.

3. Because of its structured approach to aiming, a confidence boost that helps your mind make focused “recordings” of successful shot alignments which can be more readily recalled for future similar shots (“learning by feel”).

These might not be all the benefits (see Dr. Dave’s website for a list that may go beyond these). I don’t believe any of these benefits are only available from CTE, but CTE may be the best way to get them for some players.

The controversy surrounding CTE is about whether or not it’s an “exact” system that doesn’t rely on the player’s ability to finish the aiming process “by feel”. Since nobody can seem to describe the whole process (actually, nobody can seem to clearly describe any of it past the initial half-ball alignment), it seems obvious to some (including me) that it therefore can’t really be an “exact” system and must include some (maybe a lot of) feel. For some reason, CTE users can’t stand this idea and argue vehemently against it (this may be part of the confidence thing), but their arguments always boil down to the same thing: it works for them.

I take CTE users’ word for the fact that “it works for them” and only take issue with the claim that it doesn’t involve any “feel”, but the arguments usually become unfocused very quickly and devolve to “it works” vs. “it can’t work”, giving us all lots of opportunities for playing the dozens (trading clever insults), but shedding no light whatsoever.

from SpiderWebComm (Dave Segal) (concerning Version 3 above):

– You should never sight directly down the CTEL (center to edge line). Your head should always be on one side or the other. I like pretending the CTEL is a vertical plane … my body leans against it, one side or the other.

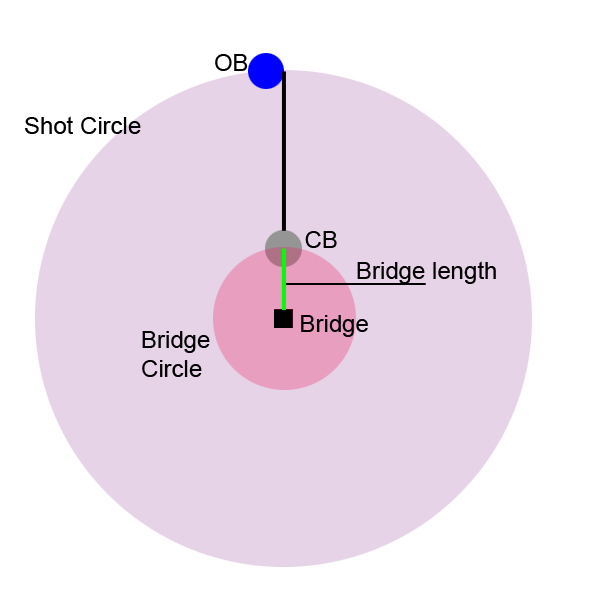

– The bridge position is not really correct in the diagram… it’s never on the CTEL. I did it this way just for simplicity in making the diagram. My only intent is to show how the shot circle works – not the other details of CTE.

Consider the following:

What you see here applies to any shot until the distance between the OB and CB is less than the bridge length. I always shorten my bridge to a distance short than that between the CB and OB when this happens. Technically, a “pivot” isn’t required at all – that’s another story … you can step into the top of the shot circle from one side of the CTEL.

If you were to rotate the cue in the bridge as a true pivot (once again, pretend a nail is driven through the point where the cue touches the skin and into the slate), the cue would turn around the bridge circle radius. This is why people miss shots completely. You would technically only turn the cue like this on a short shot.

For the “mechanical pivoters” out there, you always place your bridge first. Once you’re set in your bridge, the cue is turned along the shot circle arc, in relation to the OB – not “rotated/pivoted” from the bridge (bridge circle arc).

This is just a helpful way to describe what is really happening. This is not a functional way of playing….i.e. no one has to “see” a circle on the table in order to make any shot. This is really a “classroom” style of learning how to pivot (um, turn your cue).

OK – practical application when at the table: You should see the OB as a two-dimensional object on a vertical plane (think of the OB as a sticker on a window when down on your shot). Imagine your cue extending to the window and scrape your tip along it until you hit center ball. That’s what I do. I only “see a shot circle” on very close shots – within, say, a foot or so.

Notice the longer the shot is, the bigger the circle— the flatter the arc (think of the Earth – when you look at the horizon, it’s nearly flat). The shorter the shot, the smaller the circle— the curvier the arc (think of a basketball).

I think the reason why so many people say this is a visual system is because they “pivot to the OB” and make the shot and don’t know why.

In conclusion, the “correct” center of the CB is determined by the position of the OB, always…. not by the bridge position/bridge length.

from Colin Colenso (concerning Version 3 above):

Any cue that moves or turns from one position to another can be described as having been pivoted at some distinct point. On CTE shots this pivot point must be behind the CB and usually it is behind the bridge hand so the shape of an arc, projected to the front of the shot circle would always be flatter than the actual shot circle arc.

Hence, it seems more like the shot circle is an approximate visualization method, like, as you’ve said, scraping your tip along a distant window. This is fine, but it’s not very quantifiable or systematic, other than it would seem to indicate that you can intuitively sense the nature of the turn and that the turn pivots noticeably closer to the CB with closer distance shots.

Regarding edges of the OB, technically there is only one edge each side that is on the CTE line, but I understand that one’s perception of variations in this edge change if one sights the various angled shots from different positions relative to the CTE line.

from Jal (concerning Version 3 above):

[The dependence on pivot length] is why it’s not an exact system and why a majority of shots will be missed unless some intuitive adjustment is made. However you have the stick aligned prior to pivoting, the correct pivot point is on a line from the center of the ghostball through the center of the cueball. Where that line crosses the long axis of the cue, is the place to pivot.

Of course, if you can picture where the ghostball is located with sufficient accuracy to make the shot, on the face of it, there seems to be little point in doing the pre-alignment/pivoting procedure. That’s related to the main bone of contention between those who are critical of these types of systems, and those who support them: unless you can come up with some procedure for determining the pivot distance that’s not tied to shot geometry (impossible), the system(s) are not exact and rely on the experience and judgment of the player to make the final crucial adjustment, consciously or subconsciously.

That’s not to deny that many have found them useful.[Here’s a list of many reasons why some people find CTE and other aiming system useful.]

Dr. Dave keeps this site commercial free, with no ads. If you appreciate the free resources, please consider making a one-time or monthly donation to show your support: